The Next Anti-Abortion Tactic: Attacking the Spread of Information

With the dismantling of Roe v. Wade has come a push to crack down on speech and information about reproductive rights.

Now that abortion has been banned in more than a dozen states, abortion opponents want to stoke confusion about the legality of not just having an abortion, but even of discussing the procedure. The ultimate goal seems to be ensuring that women are unclear about their options to obtain an abortion or contraception, in their home state or elsewhere.

Signs of this trend can be found around the country. In Nebraska, law enforcement obtained a warrant to search a teenager’s private Facebook messages, in which she told her mother of her urgent desire to end her pregnancy. The mother is now being prosecuted on charges of helping her daughter abort the pregnancy by giving advice about abortion pills.

Proposed legislation in South Carolina would have made it unlawful to provide information about abortions. In September, the University of Idaho issued guidance that it might be illegal for employees to “promote” birth control or abortion. In Texas, two abortion funds (groups that help people pay and travel for abortions) this year received deposition demand letters from people tied to anti-abortion lawmakers for information on anyone who has “aided and abetted” the procedure.

And in Oklahoma, some library workers were warned about helping patrons find information about abortion, or even uttering the word. In an email, the employees were told they could face a $10,000 fine, jail time or even lose their jobs if they didn’t comply. (The library system later updated its guidance.)

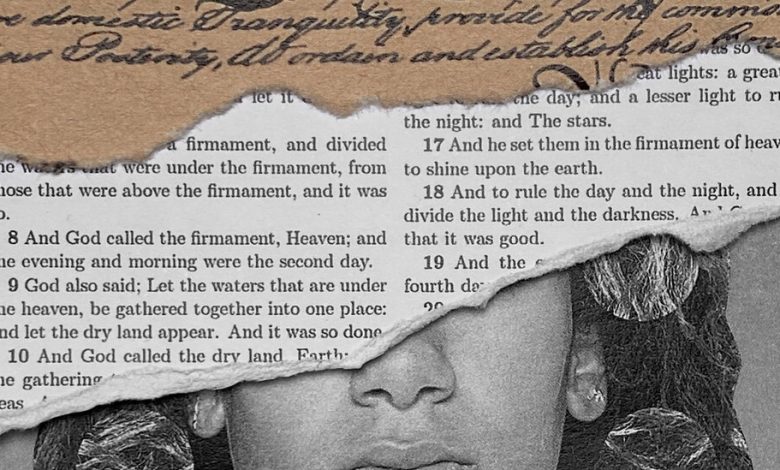

Attacks on speech about abortion may seem a sudden reversal for an anti-abortion movement that long claimed to be a champion of the First Amendment. But in fact, decades before Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the decision that overturned Roe,social conservatives set their sights on the First Amendment as a tool to chip away at reproductive rights. And it worked.

Abortion foes have long argued that the right to refuse to prescribe birth control or to perform abortions is embedded in the First Amendment and its free exercise clause, which protects individuals’ right to practice religion and dates back to speeches given by James Madison and Thomas Jefferson.

In 1873, Congress passed the Comstock Act prohibiting the mailing, sale, possession or distribution of “obscene materials,” including information about birth control or abortion provided by a physician that should enjoy protection under the First Amendment. Today, some anti-abortion activists argue that the act still applies — and trumps state laws protecting abortion.

By the 1980s and 1990s, white evangelicals flooded into the anti-abortion movement, and some, frustrated with the pace of change, resorted to lawbreaking, blockading clinics, vandalizing property and even attacking doctors. Lawyers defending the protesters invoked freedom of speech.

After the birth control method Plan B reached the market in 1999, conservatives claimed that carrying the drug, which they wrongly conflated with abortifacients, “must be left to the pharmacy.” In their view it infringed “on the pharmacist’s right of conscience,” tied to the First Amendment, if pharmacies were required to provide Plan B.

Conscience protections extend to other forms of contraception as well. Since the late 1980s,Republican lawmakers have been writing legislation to shield pharmacists who would not dispense traditional birth control, claiming conscientious convictions superseded a woman’s right to contraception. Today, six states allow pharmacists to refuse to dispense birth control, even though Plan B is considered the “gold standard” response in cases of rape.

Anti-abortion crisis pregnancy centers also have been protected by free speech concerns. When states passed laws to regulate such centers, the National Institute of Family and Life Advocates took a free-speech case all the way to the Supreme Court in 2018, and won.

Equally alarming, in the 2014 decision in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby, the court ruled that the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 permitted large, for-profit corporations to deny contraception coverage to their female employees based on the religious objections of the company’s owners. While the ruling applied only to the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate, in a bristling dissent written by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, she noted the “startling breadth” and extremity of the opinion, which she said the court could not “pretend” was demanded or required by the First Amendment’s free exercise clause.

What’s different today is that, post-Roe, the stakes have changed. More Americans lack access to abortion than before, and abortion access has everything to do with access to information. That is where anti-abortion groups are seeking an edge.

The death of Roehas given at least some abortion foes second thoughts about their proclaimed love of free speech. The National Right to Life Committee has also proposed a model law that would define “aiding or abetting” an abortion to include speech that “encourages or facilitates efforts to obtain an illegal abortion.” But conservative lawmakers don’t even need a new law: Most states already have criminal laws on aiding or abetting, and prosecutors could apply them to people who provide information about abortion.

This could be at issue in Mississippi, where the attorney general’s office recently sent a subpoena (a possible prelude to criminal charges) to Mayday Health, a health education nonprofit that put up billboards directing women to a website with information about medication abortion.

The gains of social conservatives in curtailing access to abortion are substantial. The next front of their work — hindering access to information about abortion by trampling the First Amendment rights of others — requires more than reversing a Supreme Court decision. The next frontier is interpretation of the First Amendment in ways that contradict how some conservatives have previously interpreted the Constitution, presenting new obstacles for those who wish to keep abortion accessible for women.

But as awkward as it will be to champion the speech of some while censoring others, anti-abortion leaders won’t be able to resist the impulse to try. There are already two Americas when it comes to the right to abortion, and if foes of the procedure get their way, the same will be true of the ability to exercise theFirst Amendment.

Michele Goodwin is a law professor at the University of California, Irvine, and the author of “Policing the Womb: Invisible Women and the Criminalization of Motherhood.” Mary Ziegler is a law professor at the University of California, Davis, and the author of “Dollars for Life: The Anti-Abortion Movement and the Fall of the Republican Establishment.”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.