Banned Bunnies

In May 1959, the former Alabama schoolteacher Dora Haynes Parker mused about the sexual habits and matrimonial customs of rabbits in a letter to her hometown newspaper, The Montgomery Advertiser. After sharing her bona fides — college graduate, respectable matriarch, savant about educational illustrations — Parker wrote: “Now rabbits as I know rabbits may have some problems, but not the problem of marriage. Indeed, of all the animals perhaps this family is among the most ardent practitioners of free love.”

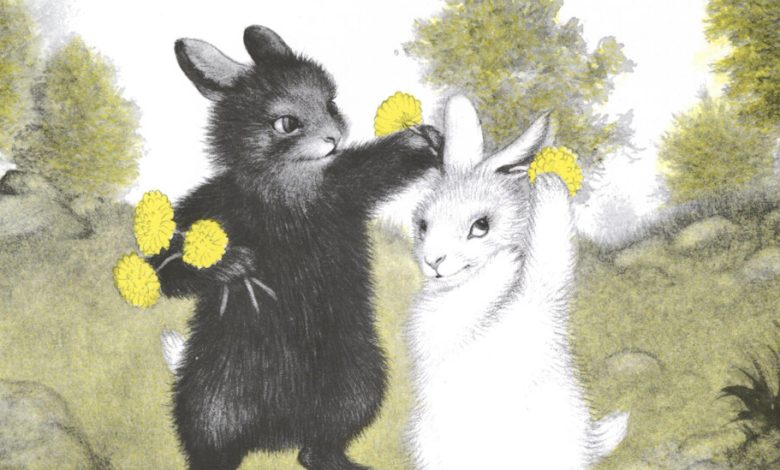

It was an odd but not random set of observations. Her letter, topped by the headline “Tell It to Old Grandma,” was both book review and pointed defense of the white South. She was adding her two cents to a nasty national argument about a 1958 children’s book, “The Rabbits’ Wedding,” by the celebrated illustrator Garth Williams.

Williams’s drawings had enlivened E.B. White’s “Charlotte’s Web,” Laura Ingalls Wilder’s “Little House on the Prairie” series and Little Golden Book titles, among many other beloved classics. But this slender picture book was his own. And it featured a cute, furry couple: a male black rabbit and his white female playmate, who becomes, over the course of the 32-page book, his bride.

The rabbits’ “interracial” union had inflamed Montgomery’s chapter of the White Citizens’ Council, whose members argued that the book amounted to grooming by literary means, conditioning preschoolers to cross the color line. Essentially a white-supremacist chamber of commerce, with a fast-growing network across the South in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education desegregation decision in 1954, the council used its dollars and clout to stoke economic intimidation and violence against the burgeoning civil rights movement. These segregationists were ideological ancestors of today’s book challengers, such as those in a Florida school district that recently banned “And Tango Makes Three,” about two male chinstrap penguins who create a family. Across time, those who ban books have shared a deep aversion to anything that promotes changing definitions of marriage and family. (Indeed, “And Tango Makes Three” has been challenged many times before.)

Ridiculous as it may sound, the brouhaha over “The Rabbits’ Wedding” made a perverse kind of sense. Children’s books often traffic in anthropomorphism, using other species to highlight human fancies and foibles: a spider crusading for a pig’s survival, that pig fretting he will become pork on a dinner table. The power of storytelling by animal wasn’t lost on the White Citizens’ Council, which roused its foot soldiers with this newsletter headline: “What’s Good Enough for Rabbits Should Do for Mere Humans.”

Nothing mobilized racial reactionaries like the prospect of “social mixing,” as it was called at the time. As Parker pointed out so helpfully in her letter, the rate-of-reproduction figures of rabbits “would indicate that the male and female rabbit, even a black male and a white female, are remarkably uninhibited.” According to the segregationists’ logic, such marriages would quickly birth generation upon generation of “rabbits” that were neither black nor white.

The book opens with the rabbits chillaxing in the woods they call home. (Decades later, Williams would dryly remark, “I didn’t say that they went to bed together.”) The white rabbit initiates bouts of leapfrog. After each frolic, the black rabbit looks “very sad.” When the white rabbit asks what’s the matter, he replies that he wishes they could be together forever. This was familiar terrain for segregationists. The notion of a rapacious Black male desire to defile the perfect lily of white womanhood had provided combustible kindling for lynching and for the murder of young Emmett Till in 1955. But, perhaps more threatening, the white rabbit is receptive. She doesn’t recoil — as a good white “woman” was “supposed” to do.

At the book’s concluding plein-air wedding, nature doesn’t revolt. Bears and raccoons celebrate.

If rabbits were stand-ins for humans — as they were in the Peter Rabbit and Brer Rabbit tales — these nuptials exploded key tenets of white supremacy. Interracial marriage would become legal across the United States with a Supreme Court decision in Loving v. Virginia in 1967, but, in the meantime, Jim Crow’s defenders would guard the institution with a siege mentality that they used to justify violence against Black children. (After all, in October 1958, mere months before “The Rabbits’ Wedding” went midcentury viral, two Black boys — ages 7 and 9 — were arrested, beaten, jailed and sent to reform school in North Carolina after playing a “kissing game” in which a white girl bussed them on the cheek. It became an international incident known as “the Kissing Case.”)

After rage-writing a 30-page response to criticism of his picture book, Williams settled on the high road in a statement saying that jaded adult minds simply could not grasp his openhearted love-is-love story. Segregationists believed they understood quite well. To them, the book portended a catastrophic swirl future: Shared schools would give way to shared bedrooms on a society-changing scale.

Emily Wheelock Reed, director of the Alabama Public Library Service Division (which lent books to local libraries), was hauled before state officials with the implied threat of funding loss. She compromised but did not cave in. Saying she found nothing wrong with the book, Reed ordered that it be kept on the agency’s reserve shelves so that local librarians visiting Montgomery could request it.

Williams’s wide-eyed innocence mimicked that of his rabbit characters: “I was completely unaware that animals with white fur, such as white polar bears and white dogs and white rabbits, were considered blood relations of white human beings. I was only aware that a white horse next to a black horse looks very picturesque.” He averred that his motivations were innocuous, just craft and thrift: A black-and-white book, with occasional pops of yellow, would cut production costs.

The retired husband-and-wife professors James and Elizabeth Wallace co-wrote the biography “Garth Williams, American Illustrator: A Life.” On a video call, the couple said that the artist was gregarious, well connected and vaguely progressive, but no activist. “His first response to attacks on ‘The Rabbits’ Wedding’ is ‘I’m just an artist,’” James Wallace noted. He added that Williams also said he “hopes children enjoy the book and that the voices of hate will never overcome the kind of togetherness ‘The Rabbits’ Wedding’ represents.”

While Williams claimed obliviousness, others perceived the potential for trouble almost instantly. Soon after the book’s publication, The Bulletin of the Center for Children’s Books commented carefully, “While the book gives a very simple concept of love and marriage, confusion could arise about marital practices in the human and animal worlds.”

Sharon Patricia Holland, a University of North Carolina professor who studies animal-human relationships and is the author of “The Erotic Life of Racism,” doubts Williams’s avowed cluelessness.

The book doesn’t even try to explain why the rabbits’ relationship is a nonstarter because, she said in an interview, there was an obvious answer. “Why is the black rabbit in such trepidation about the ask? I mean, bunnies living in the wild: Who cares? The tension in this story is the tension supplied by race.”

The controversy was good for business.Sales of “The Rabbits’ Wedding” surged, helped by the reams of opinion pieces published across the nation.

In her letter, Parker recommended that Williams stick with drawing and declared the uproar a misplaced “rabbit hunt” against white Southerners deemed “ignorant and race-minded.” A Los Angeles Mirror News headline asked mockingly, “Do Brown Eggs Bug the South?” The editorial’s author chuckled at the antics of “Faubus-like fauna infesting the region,” referring to the Arkansas governor who had tried to block the integration of Little Rock Central High School. A Black newspaper in Arkansas suggested that rabbit hutches might soon be separated by color across Dixie. And the Mississippi editor P.D. East wrote in faux earnestness, “I’ll never again look into the eye of a rabbit or a pig but what I’ll wonder what thoughts are going through their depraved minds.”

Cynthia Greenlee is a journalist and historian based in North Carolina.